Recuerdo

RecuerdoWe were very tired, we were very merry–

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

It was bare and bright, and smelled like a stable–

But we looked into a fire, we leaned across a table,

We lay on a hill-top underneath the moon;

And the whistles kept blowing, and the dawn came soon.

We were very tired, we were very merry–

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry;

And you ate an apple, and I ate a pear,

From a dozen of each we had bought somewhere;

And the sky went wan, and the wind came cold,

And the sun rose dripping, a bucketful of gold.

We were very tired, we were very merry,

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

We hailed, “Good morrow, mother!” to a shawl-covered head,

And bought a morning paper, which neither of us read;

And she wept, “God bless you!” for the apples and pears,

And we gave her all our money but our subway fares.

Edna St. Vincent Millay

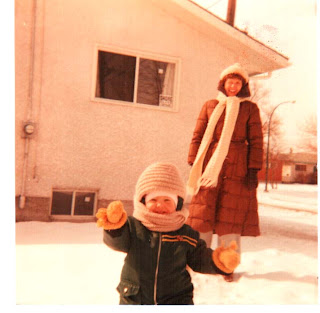

This is one of my favorite poems. It brings to mind images: night on the water, drinking coffee in empty cafes, starry lit streets; the feeling of a strong but pleasant wind blowing; images of New York, real and imaginary - glamorous, gritty, mysterious; that mood one gets in the middle of the night when you're out with friends or someone you're in love with - a wildness, a feeling of incredible happiness to be alive mixed with the knowledge that time is short so cram in everything you can, that tenuous balance between complete happiness and complete despair. And playing over everything the sound of The Bleeding Heart Show by The New Pornographers - probably because, to me, that song conjures up similar feelings.

IMAGE: "Couple watching the moonight" by Howard Sochurek